id Software: How Four Texans Invented First-Person Shooters

![]() By: Tasha

By: Tasha

Last updated: 20 February 2026, 3:13 pm

Give a man a fish, and you'll feed him for a day; teach a man to play Doom, and you'll never get another day's work out of him. Doom Press Release 1993: "In 1993, we fully expect to be the number one cause of decreased productivity in businesses around the world."

The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions. – Sigmund Freud.

UPDATED: January 2026

The Ego and the Id. You may be asking yourself what a quote from Sigmund Freud has to do with anything, but believe it or not, id and passion go hand in hand in more ways than just in the Freudian interpretation of the human mind. Were it not for the burning passion of a few talented young men brought together by sheer chance, the modern shooter genre might not exist as we know and love it today. Few game design companies have attempted to forge their own path and lived to tell the tale. Many of them fold without ever achieving their goals. Many more sell out to "Big Gaming" and are stunted in their creativity. However, once in a while, a company comes along with a "hell no, we won't go" mentality, and it pays off immensely. Perseverance is key, as well as being damn good at what you do. Such was the case with a little company known as id Software. Back in the 90s, in the heyday of shareware computer games (and bad fashion), a group of guys decided to do things their own way and wound up revolutionizing the industry and bringing the world a type of gameplay they never knew they needed.

WHAT YOU GOT IN THERE

Long before they would become the company they were destined to be, id Software sprang from humble beginnings. Initially, only John Romero was working at a small monthly subscription service run by Softdisk in Shreveport, Louisiana. I won't bore you with all of the details. Still, eventually, Softdisk ran into financial hardship because subscribers were moving away from fiddling with the rough-hewn offerings Softdisk had been producing up to this point and began wanting more. John Romero suggested they make and distribute games with a new MS-DOS disk magazine to combat this loss of interest. Thus, Gamer's Edge was born.

The original idea was to offer one to two original games monthly. This need to crank out original games quickly, in turn, led to the need for more bodies to help with the workload. However, Softdisk wasn't exactly rolling in dough, so they couldn't afford to pay workers a decent wage. So, finding quality people to fill the slots initially seemed like a pretty daunting task. However, luck was on their side, and they wound up with a ragtag group of really talented individuals that joined Romero, including programmer Tom Hall, artist Adrian Carmack, and business manager Jay Wilbur. Their ace in the hole was another young programmer called John Carmack, author of several small games, including Catacomb. Strangely, there was no relation between the two Carmacks.

Jay Wilbur, 30, was the group's older and wiser; Tom Hall was a 25-year-old programmer passionate about Star Wars and sci-fi. The young artist Adrian Carmack loved arcades and morbid drawings. But the group's core was the two Johns (Romero, 22, and Carmack, 20), two young rebels who taught themselves to code on an Apple II. Though the five guys had vastly different personalities, they all came together to form a machine that would crank out some pretty boss games.

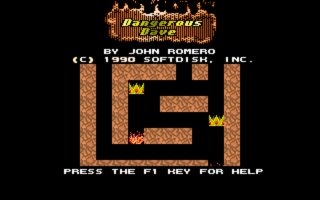

Up to this point, the team had worked under a serious time crunch, so the released games were not exactly in the most polished state; many recipients would modify them however they pleased, which was just fine with Gamer's Edge. Initially, they ported a couple of the two Johns' previous Apple II games to MS-DOS. Romero converted his platformer Dangerous Dave, while Carmack ported his top-down action-adventure Catacomb. This experience convinced Romero that there was no way to compete with Carmack regarding programming skills, and he should focus more on game design. For the next game published by Softdisk, they all worked together on a vertical scrolling shoot-'em-up called Slordax: The Unknown Enemy.

The team figured out early on that they would have a hard time offering anything truly innovative because they couldn't run fast-paced action games on MS-DOS. The reason is that, despite having more memory, a more powerful CPU, and even graphics cards capable of displaying 256 colors, the PC was not built for video games. Unlike the Commodore 64 or the NES, not to mention the Amiga, the PC didn't provide built-in graphics acceleration, fast animation routines, or hardware sprites. That's why The Secret of Monkey Island looked fantastic on a PC with a VGA card, but it was impossible to create a Super Mario Bros for MS-DOS machines.

The thing is, the id guys really loved to play games on the NES, so they could not accept this situation. Luckily, John Carmack would devise a simple solution to this problem. Instead of drawing the entire screen at each frame, he gave the illusion of a smooth-scrolling background by making the game environment larger than what was actually visible to the gamer and then moving the memory address of the top-left corner of the screen. This way, he had to draw the screen only once every eight frames, making everything manageable. Though not a new technique, per se, nobody ever did it on a PC.

He then created some optimized code to simulate in-game sprites and was off to the races. The rest of the team was in awe, and in just 72 hours, they recreated the first level of Super Mario Bros. 3 in its entirety on a PC. With this remake of sorts in hand, they decided to send it off to Nintendo of America and see what they thought. Nintendo ultimately rejected their offer to remake the whole thing for computers. This decision would come to be one that Nintendo would regret, but the crew simply moved on to the next project undaunted. They decided to make an original game with this technology.

Fortunately, their proposition to Nintendo wouldn't be their only avenue for a more significant break than Gamer's Edge at that time. Scott Miller of Apogee, the guy who "invented" the concept of "shareware", had already been somewhat of a fan of John Romero's work. However, he didn't know how to contact him without telling Softdisk. Miller reached out to the young programmer through creepy, stalker-like fan mail. After receiving several of these weird letters, Romero finally responded and gave Miller a phone number at which he could reach him. The two men spoke, and Apogee eventually struck a deal with the guys to create a three-part game as soon as they could get it to them. Miller didn't know that the guys were going to send him a revolutionary game developed using John Carmack's new technique: Commander Keen.

Tom Hall was the main workhorse behind Commander Keen's design, even going so far as to model the main character, Billy Blaze, after himself as a child. Using Cormack's workaround for a scrolling background, they decided to make the gameplay somewhat like that of Mario Bros., but with features that set it apart from other games of its type. With open exploration, a ray gun, and his handy-dandy pogo stick, Billy Blaze was definitely outside the vein of the usual platform game.

Commander Keen was a mix of sci-fi, cartoon fantasy, and Nintendo philosophy that only Tom Hall could design. The series centered on a child prodigy who built his own spaceship in his backyard, mostly from soup cans and garbage. His adventures would take him deep into space to defeat the evil aliens known as the Vorticons and protect Earth from their threats. The original Commander Keen trilogy included Commander Keen 1: Marooned on Mars, Commander Keen 2: The Earth Explodes, and Commander Keen 3: Keen Must Die!. Collectively, the games were known as Commander Keen in Invasion of the Vorticons. In usual Apogee fashion, the first part of the game was offered as shareware to garner player interest.

Upon release in 1990, Commander Keen completely changed things for Apogee and the soon-to-be id Software crew. Apogee was making about $7,000 per month. Alone, Commander Keen generated more than $20,000 in just the first month following its release. Despite the series's success, the guys did not leave their mothership, Gamer's Edge, outright. They struck a deal with Softdisk and continued cranking out their monthly subscription games (including Dangerous Dave in the Haunted Mansion) while simultaneously completing another Keen trilogy. Apogee had struck gold, and they knew it. The subsequent games would include Commander Keen 4: Secret of the Oracle, Commander Keen 5: The Armageddon Machine, and Commander Keen: Aliens Ate My Babysitter!. They would all be released in 1991. They also published a "less violent" version of Commander Keen, Commander Keen: Keen Dreams, with Softdisk.

Following their success, the guys knew they had to choose a name for themselves. They had already been going by "Ideas from the Deep." Feeling the term was too long, they shortened it to "In Demand." However, this still felt a little too long, and thanks to Tom Hall's interest in Sigmund Freud, it was eventually shortened to simply id Software. For those unaware, the Id, according to Freud and in tandem with the ego and superego, is the more primitive side of the mind and is best described as "if it feels good, do it." I personally find this two-letter moniker to be a perfectly fitting name for the company and the people who comprise it. With a new name and a new sense of the direction they wanted to head in, the boys left Commander Keen and, eventually, Gamer's Edge behind them.

IN HERE

The crew at the newly christened id Software had quite a ravenous hunger for violence and gore (save for Tom Hall, who much preferred bright, happy things). Wanting to turn their back entirely on the cutesy style of Commander Keen, they decided that their next project would be something different. They settled on a remake of the 1981 classic Castle Wolfenstein. The original Castle Wolfenstein was more about stealth than an all-out assault. However, the boys had other ideas about how the game should be played. Wanting to bring their beloved blood and gore into the gaming world, they decided to push the limits with their remake and add in many things that had never been seen before.

John Romero knew that his former Origin colleague Paul Neurath was working on a new RPG, entirely in 3D (as we know, it would be released as Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss). A remake of Castle Wolfenstein in 3D looked like a very cool thing to do, but making a 3D action game run at an acceptable speed with the hardware of those years wasn't considered feasible. John Carmack decided he could do it and worked his magic yet again. He found a way to show a 2D world with 3D graphics from a first-person perspective. It was not full 3D; there were limits: you could not look up or down, and there were no stairs or different heights, but it worked like a charm. That’s how Wolfenstein 3D was born.

The other Carmack, Adrian, decided it was time to abandon the 16-color EGA palette and move to VGA with 256 colors. This significantly improved the visuals, enabling Adrian to add more blood and special effects.

Wanting this game to be a fast-paced thrill-fest, they decided to keep the story to a minimum and focus on the gameplay. Playing as a captured Allied spy, you need to escape the clutches of your nazi captors and foil their plans for world domination. You can accomplish this task by gunning down any nazis in your path. The game ultimately ended up featuring many violent and gory elements, such as pools of blood and skeletons accompanied by realistic gunfire sounds and the screams of dying enemies. The stealth element of Castle Wolfenstein was entirely dropped.

When Miller saw the game, he realized it was going to be a hit. He convinced the guys to prepare five paid episodes. As with their previous games, Apogee released the first chapter for free, and it took off from there. After its 1992 release, Wolfenstein 3D went viral and quickly spread worldwide. The crew at id Software literally outdid themselves. It wound up significantly surpassing the sales record they had set with Commander Keen, generating more than $200,000 per month with this new game. Some reviewers criticized the disturbing violence of Wolfenstein 3D, but this didn't prevent the game from becoming a success.

In addition to the shareware model, id Software also tested the boxed games business, selling the seventh Wolfenstein episode, Spear of Destiny. It was published by FormGen and released in September 1992. In the end, even Nintendo returned to them, asking for an SNES version of Wolfenstein 3D. After facing Nintendo's strict censorship during this conversion, the guys decided never to work with Nintendo again.

Wolfenstein 3D is largely credited with helping create the first-person shooter genre and shaping what we know and love today. However, id Software had no intention of stopping there.

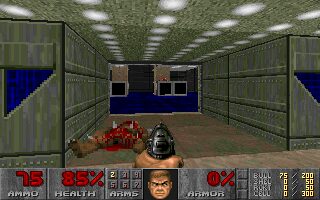

DOOM

Still riding the high of Wolfenstein 3D's success, the guys decided that Apogee would not publish their next game. They had enough money and experience to go alone.

Tom Hall would have wanted another Commander Keen trilogy, but the others could not go back to cute fantasy action games after Wolfenstein 3D. They wanted to create a new, more violent, dark, bloody, and technically advanced shooter. Mixing their passion for the Alien movies and the Dungeons & Dragons campaign they were playing, crammed with demons, they ended up with an idea about demons in space. Taking its name from a line delivered by Tom Cruise in the movie "The Color of Money," they named it Doom. It was going to take the gaming world by storm.

Development of Doom required a full year of intense work, from January 1993 to December 1993. Tom Hall started to work on the game design and the story, but this would not be a game based on storytelling. He clearly could not continue working with the others; their views were too different. Tom would leave the company before the shooter was completed, in August 1993. No doubt saddened but still largely undaunted, the remaining crew would push forward with their new project.

In keeping with their model of 'less story, more action," Doom had a very loose story to set the stage for your descent into hell. You are a marine working for Union Aerospace Corporation (UAC) and sent out to an out-of-the-way research facility as punishment. Little do you know, you are about to walk into an utterly FUBAR situation. Luckily for you, space marines have a massive arsenal at their disposal so that you can decimate the minions of hell in various ways.

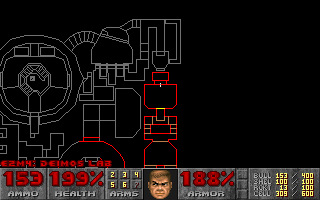

Always looking to outdo himself, John Carmack yet again created his own game engine to allow for the features that id Software was after. First, the game took advantage of hardware advancements: the minimum requirements for Doom were a 386 processor with 4 MB of memory, while Wolfenstein was fine with a 286 and 640 k. But most of the improvements must be ascribed to John Carmack's new programming skills.

It was still not fully 3D (some called it 2.5D), but the new engine enabled more immersive effects, leading to more varied and complex level design. Stairs and floors at different heights were finally possible, as well as more varied angles, even if the walls still had to be vertical. The level design was much more interesting; it was possible to create traps with monsters at different heights.

The lighting effects alone created varying conditions that helped amplify the creepy atmosphere Doom was aiming for. Also, the physics of all the objects, including bullets, was much more realistic, and the AI of the monsters was more advanced. There were also levers, doors, keys, and switches. Not mentioning the automap. It was a much more mature and complete game.

To help John Romero with the level design, after Tom Hall left, the guys hired Sandy Petersen, the creator of the tabletop RPG Call of Cthulhu. If Doom has a fantastic level design, it's also thanks to him.

With their desired level of action and violence firmly in place, id Software decided to add yet another feature that had never been done in the genre before. Feeling that multiplayer was the future of gaming and that with the emergence of the Internet, it was the natural next step, John Carmack implemented Novell's IPX networking protocol, transforming Doom into a fantastic new experience. If the single-player mode was great, the multiplayer game, especially the Deathmatch mode, was unique. John Romero was right when he said, this is going to be the fucking coolest game that the planet Earth has ever fucking seen in its entire history.

Through previews and press releases, players were practically chomping at the bit to play the next thing from id Software. In keeping with tradition, they offered the first part of the game as shareware, and people waited for the game to go live with bated breath. The release date was set for December 10, 1993, at midnight. However, the game was so highly anticipated that the studio couldn't even upload it because so many people were already logged in and waiting. They had to kick everyone off, even to upload Doom, and within minutes, the server crashed under the sheer volume of traffic trying to access the game. It was a veritable feeding frenzy, and this was only the beginning. In the following weeks and months, companies, high schools, and universities had to ban Doom, at least in multiplayer mode, because it made the networks unusable.

Jay Wilbur decided that the first episode could be distributed by anyone, for free or not, on disks or any other way. It was a brilliant move. Doom conquered the entire world. Even if only a tiny percentage of the people who played the first episode went on to buy the others, our friends at id Software would still become very rich. John Carmack and John Romero both celebrated buying a Ferrari Testarossa.

The hunger for Doom didn't die after reaching the masses. It became even more popular and practically became a living, breathing thing. It gave way to too many copycats and cloners to attempt to cash in on the hysteria. However, there was no outdoing the original.

When DOOM II: Hell on Earth was released on October 10, 1994, it wasn't uploaded to an unknown server. This time it was launched with a $2mln marketing budget. A big press party called "Doomsday" was held at a gothic nightclub in New York City. It was a success. According to the forecasts, the distributor had prepared and sold more than 600,000 copies to the stores, enough for three months. But they ended in one month. Sometime later, id Software deposited its first royalty check to the bank: $5 million.

Doom is considered one of the best games ever made. It is credited with popularizing multiplayer in FPS games and giving birth to 3D gaming. With Commander Keen first, then Wolfenstein 3D, and finally Doom, id Software demonstrated that the PC was not only a suitable platform for games but was the platform for playing video games. The Amiga and Atari ST were already struggling, but like it or not, Doom completely erased them.

Many people consider gaming to have two distinct eras: pre-Doom and post-Doom. Opinions on whether Doom had a positive or negative impact on gaming remain polarized, but opinions aside, there was no denying that id Software changed the industry once again. I must admit that I am 100% guilty of owning just about every iteration of Doom there is on offer. I myself love the game and continue to play from the very first Doom to the most recent. But far be it from id Software to stop there.

TELEFRAGGED

To say that the Doom franchise was a success is an understatement. Some companies might have taken that success and ridden it off into the sunset, but id Software was never one to rest upon its laurels.

For the next game, the inspirations were the Star Trek holodeck, William Gibson's novel Neuromancer, and the virtual reality games that started appearing in the arcades. The title Quake came from the character Carmack was interpreting in a D&D campaign. The two Johns already talked about a 3D dark fantasy game where the primary weapon would be the "hammer of thunderbolts". Now was the time to make it real, with a complete 3D engine and internet play. Carmack wanted to create an immersive and persistent online world. But this would be much more challenging than he thought, not just because of technical complexities.

In the meantime, the team had grown. Carmack convinced a talented programmer, Michael Abrash, to leave Microsoft to help him. Another new entry was American McGee. He was hired to help Romero with the design of Doom II. In the end, he made more levels than Romero, who was busy with many parallel projects, including his support for Raven Software's Heretic and Hexen (games based on the Doom engine).

Once Doom II was completed, the team could focus on Quake. But by the middle of 1995, the new game was still a long way off. Carmack and Abrash were working on the engine, while Romero worked on other things. Adrian Carmack was working on some Gothic and Aztec designs for the new game, but he was frustrated by the lack of progress.

By the end of the year, everyone was unhappy except Romero. He thought there was no hurry; he said he would start working on the design once John Carmack had completed the engine. But the others started complaining about Romero's project management. They could not continue without a design document. Carmack was really struggling with the engine, and for the first time, he also started to doubt Romero. The two realized they were no longer a single mind. Carmack thought Romero was no longer passionate about programming, and Romero thought Carmack was no longer passionate about playing games.

Ultimately, they decided to drop the idea of a fantasy game and go back to something less innovative: a sci-fi shooter, a sort of new version of Doom, but using the new 3D engine. Romero was unhappy, but he had to accept.

In the meantime, sales of Doom II and Ultimate Doom on Christmas 1995 generated millions, and id Software's earnings doubled.

With the new Quake idea finally in place, id Software spent the first months of 1996 in crunch mode, trying to complete the game as quickly as possible. With increasing tension among the team and working 16 hours a day, there was no fun left. To make things worse, Carmack decided that the starting levels of Quake would be designed by Tim Willits, a guy who arrived from the Doom mod community.

Finally, in June 1996, the most anticipated computer game of all time was completed. But the day John Romero uploaded the first shareware episode on the server, June 22, 1996, he was alone in the office. Soon after, in August, Romero was asked to leave the company. It was the end of an era.

Like Doom, Quake kept the concepts of action, hidden areas, and decimating enemies with heavy firepower. The game's premise was very similar to Doom in that you play as an unnamed protagonist sent through an experimental portal to deal with whatever is on the other side. As the only surviving member of your squad, it's your job to keep the creatures from reaching Earth.

Despite the troubled development process, Quake garnered critical acclaim and strong sales, though it would not replicate the success of Doom II. The main innovations were the complete 3D engine with polygonal enemies, realistic lighting, and improved physics. Not only that, but it was also one of the first games played on the Internet, even though at the time it was much easier to play on local networks (LANs).

In fact, what players appreciated most was the multiplayer deathmatch mode. Quake allowed one-on-one duels, team play, and free-for-all competitions. LAN parties became so popular that companies started organizing them and inviting people to watch the match on big screens.

Not only did id Software launch the PC gaming industry, but it also helped launch the eSports phenomenon with Quake.

Unfortunately, Quake would be the last game created by the core group before they would go their separate ways. In 1997, other members left, including Jay Wilbur, Abrash, and Petersen, while John Carmack began working on Quake II.

TODAY

Much like a firework, id Software rocketed into the sky, dazzled the world, then faded away.

It's strange to think that id Software still exists, yet no member of the original team is associated with it. However, this doesn't mean that all of them are out of the game. Tom Hall has enjoyed a long and fruitful career. He was first working at Apogee after the initial breakup with id in 1993. In the 2000s, he reunited with John Romero for a while, founding Ion Games and then Monkeystone Games. Hall and Romero worked together on the cult game Anachronox. Unfortunately, those two companies folded, so he and Romero worked for Midway Games until they parted ways again. After Midway, Tom would work for KingsIsle Entertainment. However, he would only stay there for one year before finding his current home at PlayFirst.

After bouncing around in the 2000s, John Romero would eventually open a company with his wife, Romero Games, in 2015. Romero Games is still going strong. Their last title is the strategy game Empire of Sin. Currently, Romero is offering a special Doom II level whose proceeds go to the Ukrainian Red Cross and the UN Central Emergency Response Fund.

Adrian Carmack stayed at id to work on Quake II and Quake III: Arena. He also made the art for 2004's Doom 3 and left id Software in 2005. He is no longer in the game industry. Jay Wilbur joined Epic MegaGames and helped create the Unreal games.

John Carmack stayed at id Software the longest after everyone else left. He remained with the company until he became interested in the Oculus Rift. Due to disagreements, he left the company in 2013 to join Oculus VR. As a man of many talents, gaming is not the only passion of Carmack. In the 2000s, he developed a love of rocketry. So much so that he founded his own company, Armadillo Aerospace, with the goal of achieving suborbital spaceflight. Currently, he is investing most of his time working on Artificial General Intelligence. Though he's out of the gaming industry, his gaming engines are still used to make shooter games like Call of Duty and Half-Life.

There is no denying the impact that id Software has had on the gaming world. They came along, spun the industry on its ear, and it has never been the same. I am among those thankful for their contributions and will continue to enjoy the fruits of their labor for years to come.

If you want to read more about id Software, we strongly recommend the book "Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture" (see link below).